|

An interview with Aydin Aghdashlou, on the concept and examples of “the national cinema of Iran”

A Missing Immediate Memory

by Massoud Mehrabi

|

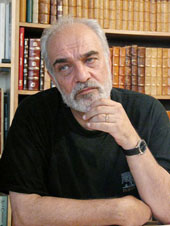

A lot of heated debates have been going on in Iran’s press and cinema community recently on the “national cinema.” A number of such debates took place at a conference sponsored by the Iranian Society of Film Critics. The conference was entitled “National Cinema, a Roadmap for Tomorrow.” A series of articles published in the Film Monthly magazine (Film International’s Persian-language counterpart) were instrumental in promoting the discussions. The articles generally maintained that there were distinct national characteristics in some Iranian films, but the number of such films was not large enough to indicate a trend towards a national cinema. This is the most outstanding interview that appeared in the series: An interview with Aydin Aghdashlou, who teaches the history of arts and apart from being the country’s best known connoisseur of arts, is a master painter and author of highly informative articles including film reviews. His analytical critique of Oliver Stone’s Alexander and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, as well as his article Video Art: Cinema or Art have appeared in the previous issues of Film International. A lot of heated debates have been going on in Iran’s press and cinema community recently on the “national cinema.” A number of such debates took place at a conference sponsored by the Iranian Society of Film Critics. The conference was entitled “National Cinema, a Roadmap for Tomorrow.” A series of articles published in the Film Monthly magazine (Film International’s Persian-language counterpart) were instrumental in promoting the discussions. The articles generally maintained that there were distinct national characteristics in some Iranian films, but the number of such films was not large enough to indicate a trend towards a national cinema. This is the most outstanding interview that appeared in the series: An interview with Aydin Aghdashlou, who teaches the history of arts and apart from being the country’s best known connoisseur of arts, is a master painter and author of highly informative articles including film reviews. His analytical critique of Oliver Stone’s Alexander and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, as well as his article Video Art: Cinema or Art have appeared in the previous issues of Film International.

Film International: The idea of national cinema remains untouched as a topic in the Iranian literature on cinema. Film journalists in Japan, India, France and some other countries have worked on it. This interview could be an introduction to that topic. Do you believe in the notion of national cinema? If yes, how does that relate to the idea of local cinema?

Aydin Aghdashlou: As you have observed the division, there are two different worlds with different stances on national cinema and national arts for that matter. Since the 19th century when modernity, industrial revolution and Western colonialization found their way into this part of the world, the Western world virtually brought the rest of the world under its domination. I usually do not speak about the Western world because the notion has been so generalized that it has lost its meaning. This domination and replacement is part of the nature of the Western world. It drew a dividing line between the world that has suggestions to make and offers things and another world that has no suggestions to make and consumes things. This was even more elaborate in the 19th century. Everything that comes from the other side is a national thing that becomes a global thing. As an example, take Western movies or cop movies or the cinema that was prevalent in the States in the 1940s. Such a cinema exports the list of its problems to other parts. Perhaps, we could say that those were the national cinemas. But their national cinema would not remain national. It turns into world cinema when it is exported and transported. So, there is a dividing line here. How can we find our own national cinema? The answer is a bit complicated. By "we" I also mean Japan, India and Egypt. They are all the same. We try to find our place within the context of the world cinema that has been presented to us and is a mixture of all of the national elements of where it comes from. Thanks to its extraordinary replacing power, soon it will be turned into our national cinema. In other places, in particular in Japan, it becomes such a strong national cinema that still carries forward its power of expansion and replacement.

FI: Does it have the power of expansion and replacement?

AA: Yes, exactly, it has. In order to look closer, we should define national cinema in our part of the world. Whatever they had, from "comedia del arte" to vaudeville, opera, musicals and so on, which later became the foundation of Hollywood cinema, all came from the stage. All of their artists came from the theater. Look at Charles Chaplin's family. They could present all of their shows as cinema and publish the same all over the world rather quickly. Cinema expanded quickly because it could be transported. In silent cinema, even language was not a problem. That was how Hollywood started to change the shape of the world. It had blueprints for your taste and lifestyle. French cinema was like that too. The idea of Jean Gabin smoking cigarette while beating other men reflected the French way of life at that time. So, it turned into national cinema and became global cinema almost immediately. But it is different with us and the Japanese.

FI: Where is this difference? We are also a nation with an age-old history…

AA: If we look at the history of the Iranian cinema, and you know its history better than me, we would see that its serious history starts in the second half of the 1960s. In the Iranian cinema of that period, there were issues that were not discussed in earlier films. As we did not have real national theater, our true theater was passion play. Before and in the early days of the Iranian cinema there were plays on the stage in Iran that had been adapted from European plays, like Noushin and Sa'di Theater. We had to define national cinema from the scratch. And it was not only for cinema, we had to define the term national for painting, music and poetry too. I am not suggesting where we should look for it. However, undoubtedly there was a search going on for this meaning. This search became a national preoccupation and the issues of national identity, national art, national culture and the like are still relevant.

SUBSCRIBE

[Page: 72]

|

|

|

|

|

President & Publisher

Massoud Mehrabi

Editors:

Sohrab Soori

Massoud Mehrabi

Translators:

Sohrab Soori

Behrouz Tourani

Zohreh Khatibi

Contributors

Shahzad Rahmati

Saeed Ghotbizadeh

Advertisements

Mohammad Mohammadian

Art Director

Babak Kassiri

Ad Designers

Amir Kheirandish

Hossein Kheirandish

Cover Design

Alireza Amakchi

Correspondents

E.Emrani & M. Behraznia (Germany)

Mohammad Haghighat (France)

A. Movahed & M. Amini (Italy)

Robert Richter (Switzerland)

F. Shafaghi (Canada)

B. Pakzad (UAE)

H. Rasti (Japan)

Print Supervisors

Shad-Rang

Noghreh-Abi

Gol-Naghsh

Subscription & Advertising Sales

Address: 10, Sam St., Hafez Ave., TEHRAN, IRAN

Phone: +98 21 66709374

Fax: +98 21 66718871

info@film-magazine.com

Copyright: Film International

© All rights reserved,

2023, Film International

Quarterly Magazine (ISSN 1021-6510)

Editorial Office: 5th Floor, No. 12

Sam St., Hafez Ave., Tehran 11389, Iran

*

All articles represent views of their

authors and not necessarily

those of the editors

|

|

|